From the horse-drawn carriage to metropolitan transportation

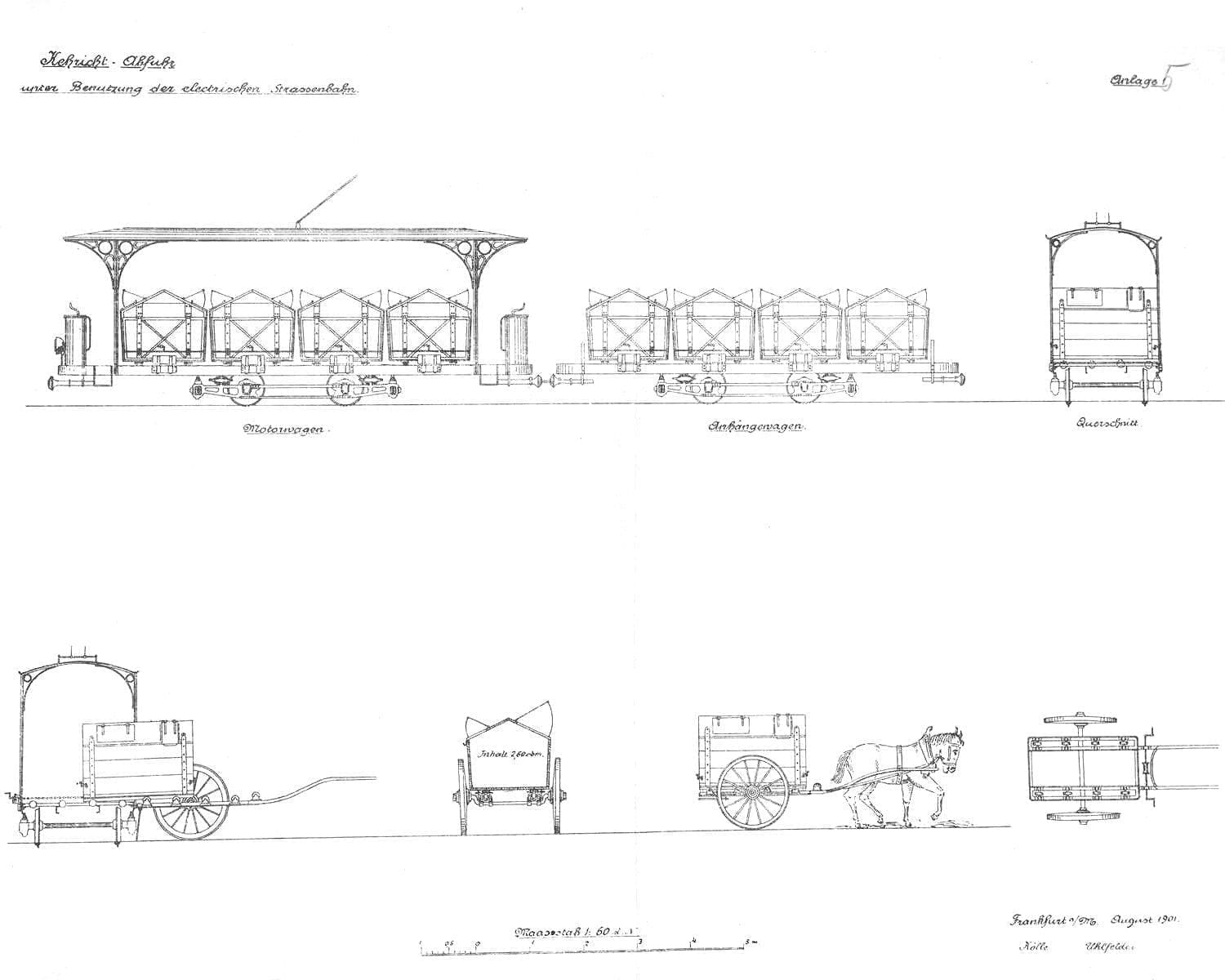

To the year 1839 can be traced back to the beginning of Frankfurt’s public transportation system, at least in the sense that it offered rides to everyone. For on 06.09.1839 Frankfurt’s first railroad station was opened and given the name “Taunus-Bahnhof”. Not because it led into the Taunus, but rather along it. The station was one of the two end points of Hesse’s first railroad line, which ran from Frankfurt to Wiesbaden. The station was located on the Gallusanlage between Taunusstrasse and Kaiserstrasse, although the latter two did not yet exist at the time.

On the occasion of the opening and in anticipation of increased demand for transportation, a consortium led by the entrepreneur Benjamin Roth applied for a concession for a private horse-drawn omnibus service. November 1, 1840 was granted. The haulier Daniel Keßler had already applied for a license on August 2, 1839 his vehicles did not operate according to a fixed timetable on the same routes, which meant that this operation did not correspond to the later definition of regular services.

However, neither company flourished particularly well, as many journeys in Frankfurt could still be made quite easily on foot due to the short distances, on the one hand, and because the coachmen tried to steal the few customers who could afford such a service from each other, on the other. Despite this, Roth and his 8 co-founders earned quite well from their “cab company”, as it offered other services in addition to regular services. For example, hiring out carriages, including coachmen, to wealthy citizens who did not want to maintain their own carriage brought them more profit, so that regular services no longer played a major role for them.

1862 a new push was made in the direction of scheduled services, today one would say: a new start based on an improved concept. The Roth family joined forces with 4 other entrepreneurs to form the “Frankfurter Omnibusgesellschaft” (“FOG”). This was awarded the concession for two (horse-drawn) omnibus lines, which started operating on June 11, 1863.

Line “A” ran from Bockenheimer Warte to Hanau station via the Zeil, while line “B” ran from Westendplatz via the “Westbahnhöfe” at Gallusanlage, Roßmarkt and on through the old town via the “Mainbrücke” (today: Alte Brücke) to Offenbach station in Sachsenhausen, which later became the local station. One year later, 5 lines were already in operation, although additional lines had to be discontinued shortly afterwards due to a lack of profitability. However, there were soon 3 lines again, with a new line from Konstablerwache to Bornheim.

Despite all this, the company was not profitable in the long term, with frequent fare changes – sometimes up, sometimes down – in an attempt to turn a profit. It also sold vehicles, some of which ended up in Brussels due to this financial crisis.

“Public transport” in today’s sense of the word actually only came about after a concession was awarded to the company Donner de la Hault & Cie. in Brussels for the “construction of a tramway”, which was intended to finally fulfill the expectations of all those involved. Namely, the expectations of citizens and tourists for reliable, comfortable transportation at reasonable prices, as well as those of the city administration to be able to exert influence on the concessionary company through special contractual regulations, among other things to be able to better control the further development of the city. Last but not least, the expectations of the company owners to achieve an acceptable, adequate return.

The company Donner de la Hault & Cie. began laying tracks immediately after the concession was granted and opened on 19.05.1872 the first line of the horse-drawn railway (> Network map 1872) [PNG, 326.38 KB] from Schönhof to the Hauptwache. Compared to the horse-drawn omnibuses that had previously rumbled over the ubiquitous cobblestones, the horse-drawn streetcar offered a much more comfortable ride as well as cheaper fares, which had a significant impact on its success.

In the years that followed, citizens frequently asked when their own neighborhoods would finally be able to enjoy comfortable, modern transportation. Although not all of these requests could be met, a dense rail network was nevertheless created over the next 25 years, which by 1900 already had 15 routes with just as many lines. Starting from scratch in 1872, the FTG had managed to build up a 30.5 km long rail network in the 25 years of its existence up to 1897, which formed the basis for the local transport of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, development picked up speed. 1848 two further stations were built parallel to the Taunus station: Main-Weser and Main-Neckar stations, collectively referred to as “western stations” because they were located to the west of the city area at the time. However, the stations were soon no longer able to cope with the rapidly increasing rail traffic and larger replacements were needed. A major project was planned in the 1980s and built by Hermann Eggert, the architect in charge. Finally, on 18.08.1888 the new “Centralbahnhof”, today’s main station, was opened. It was the largest in Europe at the time and soon became a catalyst for further urban development.

Of course, the FTG also had to rise to the challenge and build a line there, which was put into operation at the same time. Along with the advancing industrialization and economic development, and parallel to this the rapidly increasing population, Frankfurt gradually expanded far beyond the medieval city limits. As a result, the transport network had to adapt to the challenge, and after the takeover of the FTG into municipal control in 1898 and the electrification of the horse-drawn streetcar lines, the streetcar tracks penetrated further and further into the outer districts.

USE THE STREETCAR FOR GARBAGE COLLECTION?

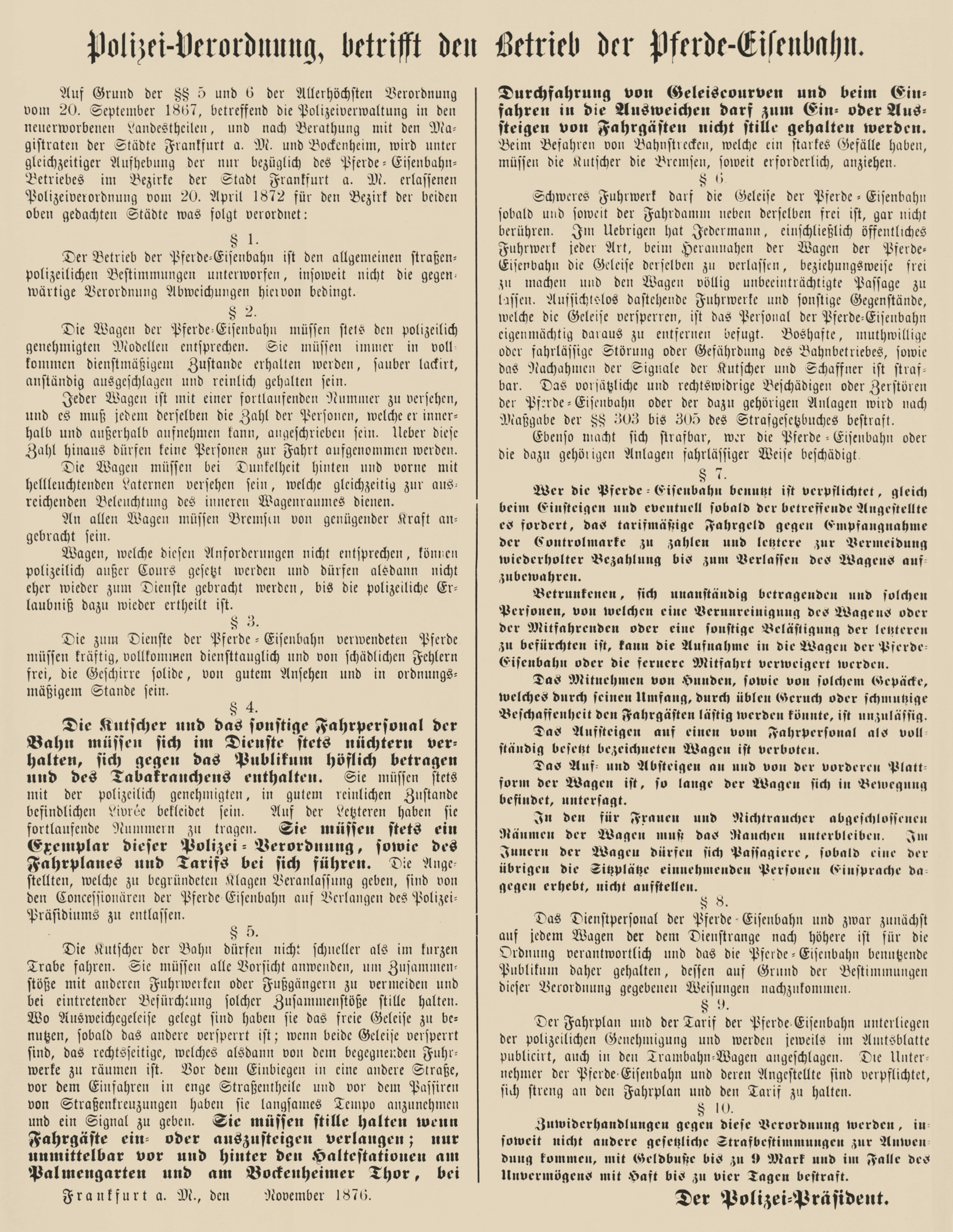

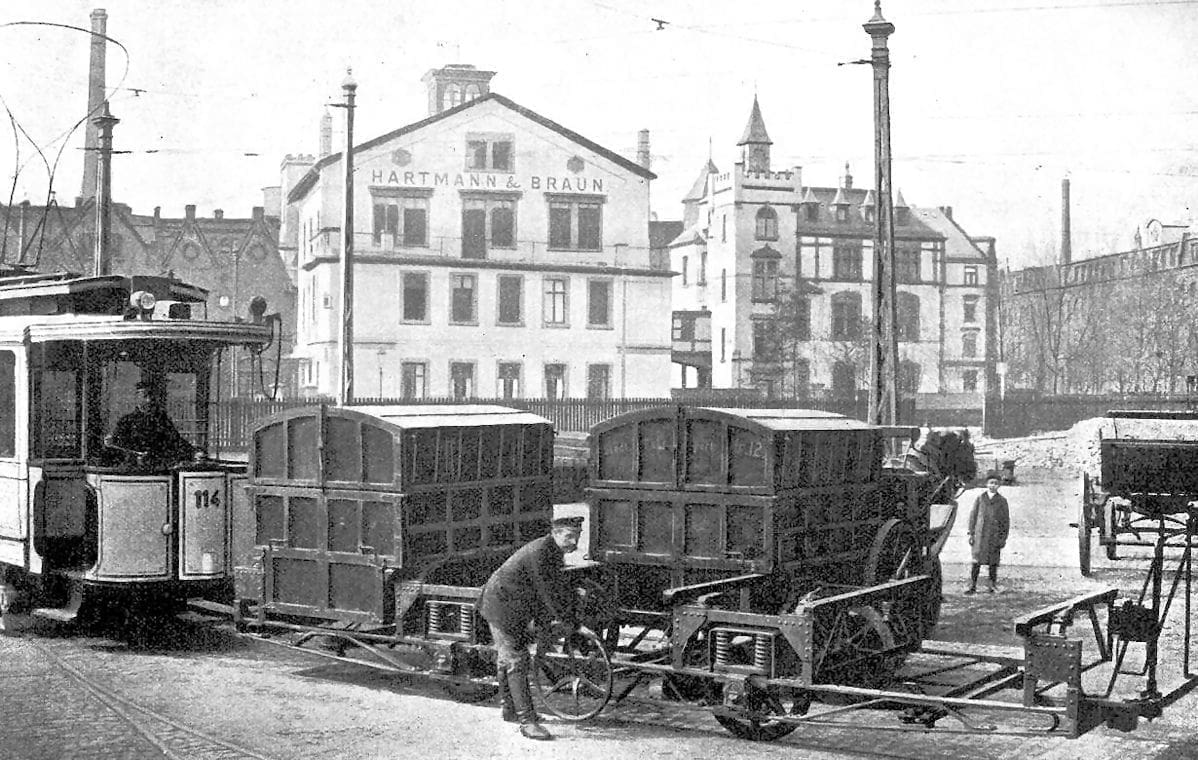

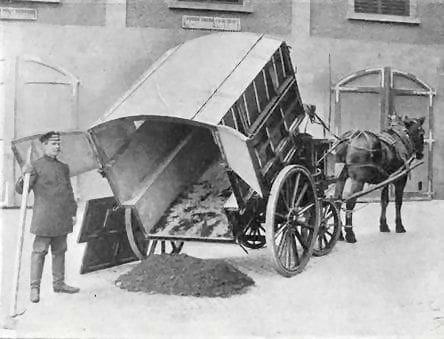

While the horse-drawn tram lines were still being electrified, other possible uses for the new means of transport were already being considered. When planning the waste incineration plant (MVA) in Niederrad (1901 – 1905), waste transportation by streetcar was envisaged, even calculated in terms of costs and included in the calculation of profitability. Five refuse trains, each consisting of a special motor car and two sidecars, were to be procured. In 1901, the civil engineering department had reported in detail to the magistrate on the possibilities of waste incineration. Several tons of Frankfurt’s household waste were taken to Hamburg on a trial basis, where a waste incineration plant had been in operation since 1893 and where the calorific value and composition of Frankfurt’s household waste had been precisely determined.

Around 4/5 of the city’s daily waste volume of around 300 m³ at the time, i.e. around 240 m³, was to be transported to Niederrad by streetcar from collection or reloading points in the city area. Special containers were provided for this purpose, which could be transferred from horse-drawn carts to special streetcar cars in a few simple steps. The calculation envisaged that each refuse train would transport four containers of 2.5 m³ each, i.e. a total of 30 m³. This meant that four trains plus a reserve train would have been needed to handle the 240 m³ of waste, each of which would have had to make two trips per night from the reloading points to Niederrad during the non-operational period between midnight and 5 am.

There was apparently at least one prototype of a refuse trailer, but the project never got beyond the experimental stage. In 1910, when the incineration plant was commissioned, waste was delivered exclusively by horse-drawn vehicles, which repeatedly led to complaints from residents along the access routes due to the traffic at night. Nevertheless, in 1912, the municipal authorities informed the complainants that the use of streetcars was not planned for the time being.

As the municipal waste disposal department had to hand over around a quarter of its horses to the military at the beginning of the First World War, the transportation of waste by streetcar seems to have been considered again; after all, a connecting track was laid from Haardtwaldplatz to the waste incineration plant through Kalmitstraße in 1914. Nevertheless, there was no regular waste transport on the streetcar. For one thing, there were no suitable collection and reloading points with sidings on the network; they would have had to be built away from the residential areas. Secondly, the streetcar authority had reservations because operations would have had to be restricted. On the southern Main lines, it would have had to end earlier/start later in order to free up access routes for the refuse trains to the waste incineration plant. There were considerable objections to this.

In 1923, the city council decided to shut down the waste incineration plant. From 1925, the waste was no longer incinerated but stored in several smaller landfills in the city area, until finally in 1928 a large landfill was created in the city forest, which was later known as “Monte Scherbelino”. After the war, the calorific value of the waste had fallen so much that it could no longer be incinerated without support firing, i.e. the addition of coke or wood, or it became uneconomical. The waste incineration plant was therefore shut down in 1925 and demolished shortly afterwards. The siding in Kalmitstraße was extended in 1928.

All images & graphics relating to the Mülltram: ISG, Magistratsakte 2.169 Bd. 1

Almost 80 years later, the municipal council addressed this issue again and responded in detail to a

suggestion of the local advisory council 8 [PDF] on the possibility of supplying the MHKW Heddernheim > via the light rail line [PDF].

THE “ELECTRIC” IS SPREADING

Even before the I. Even before the First World War, the network had expanded to 97.5 km of track and 212 km of track. In order to keep pace with the overall development, three times as much was built in the 14 years between the turn of the century and the war than in the period twice as long before. This is particularly remarkable in that the figure alone does not show that it included suburban lines and various bottlenecks with a rather spartan construction standard typical of the time (sparsely laid out, largely single-track and only provided with turnouts where absolutely necessary). Instead, the pairs of tracks were concentrated in the area of turning points and depots.

The route network generally reached its greatest length of 125.7 km before the Second World War, plus the 75 km of the bus network that had been created in just 15 years since 1925. A total route network of over 200 km, more than the distance between Frankfurt and Kassel. The track length of over 265 km was never exceeded again.

With the outbreak of the First World War, however, development came to a complete standstill for the next few years. The development was also described by the tramway management, in great detail in this commemorative publication for the 50th anniversary:

FRANKFURT’S LOCAL TRANSPORTATION BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS

In the first few years after the end of the First World War, the German Reich was confronted with the demands of the Allies, which were finally incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles in May 1919, which came into force at the beginning of 1920 and imposed high reparations payments on Germany. The tramway could therefore 1919 the construction of the Berkersheim line, which had already been planned before the war, but which was not completed until 1925 could take place.

1922-23 were also characterized by the consequences of the war, inflation and a shortage of goods. A shortage of coal led to the temporary closure of the Waldbahn; under the given circumstances, there was also no question of investing in the wagon fleet and route network. Conditions only slowly improved again from the end of 1923, after the introduction of the Rentenmark. The text below shows that a turning loop at the Riederhöfe was imminent. Unfortunately, the date of its opening is unknown. However, the construction of the above-mentioned tracks is mentioned here as a condition for the extension of line 18, which was to run from July 1924 to Borsigallee from July 1924. From this it can be concluded that the loop was either put into operation at the same time or was already in place earlier, which means that it could have been built in 1923 or -24.

1924-25 Once conditions had stabilized, investments could be made again. An extensive conversion program was launched, many older railcars became work cars, the remaining railcars with open platforms received glazing or were converted into electric railcars. The previously unfinished line to Berkersheim has now also been opened. The new stadium was connected to the tramway in two stages, after which the Waldbahn coming from Schwanheim ended at Oberforsthaus. An order was placed with various manufacturers for 50 new (F) motor coaches and 50 new trailer coaches, the first partial delivery was made within 1925. The “Frankfurter Nachrichten” published an article on July 12, 1925 on July 12, 1925 about the imminent introduction of bus lines in Frankfurt (source: HSF archive). After delivery of these vehicles, the first line (A) started on 07.10.1925 and three more lines were added the following year.

1926-27 further line extensions followed, including the installation of further switches on the single-track Praunheim line, the loop at Ostbahnhof, a block bypass at Rödelheim station, a postal track at the main station, etc.

The delivery of the F-trains is completed with Tw 450 and Bw 1550. The city of Höchst introduces its own bus service, which is also expanded to four lines in the course of the next two years. This brought Höchst into line with Frankfurt. However, the concessions were already summer of 1928as part of the incorporation of Höchst into the city of Frankfurt.

Offenbach opened its third streetcar line in 1928, which ran from Marktplatz via Waldstraße to the south.

1928-29 A very serious accident in 1928 resulted in many deaths and injuries. A 3-car train on line 18 collided with a harbour streetcar at the Lahmeyerstraße/Am Erlenbruch track crossing. In 1929, the streetcar line from Riederhöfe to Fechenheim was opened and other lines were upgraded to double track. In addition, the forest railway lines from Ziegelhüttenplatz to Neu-Isenburg and from Oberforsthaus to Schwanheim were electrified and integrated into the streetcar network. The economic situation had normalized to such an extent that the company was once again able to focus on rationalization and technical innovations. A further order for vehicles was initiated, 30 G series trams and 110 Bw trams were ordered from 4 different manufacturers and were delivered in these two years. Their order was based on this magistrate’s bill (Source: ISG, magistrate’s file R1.714).

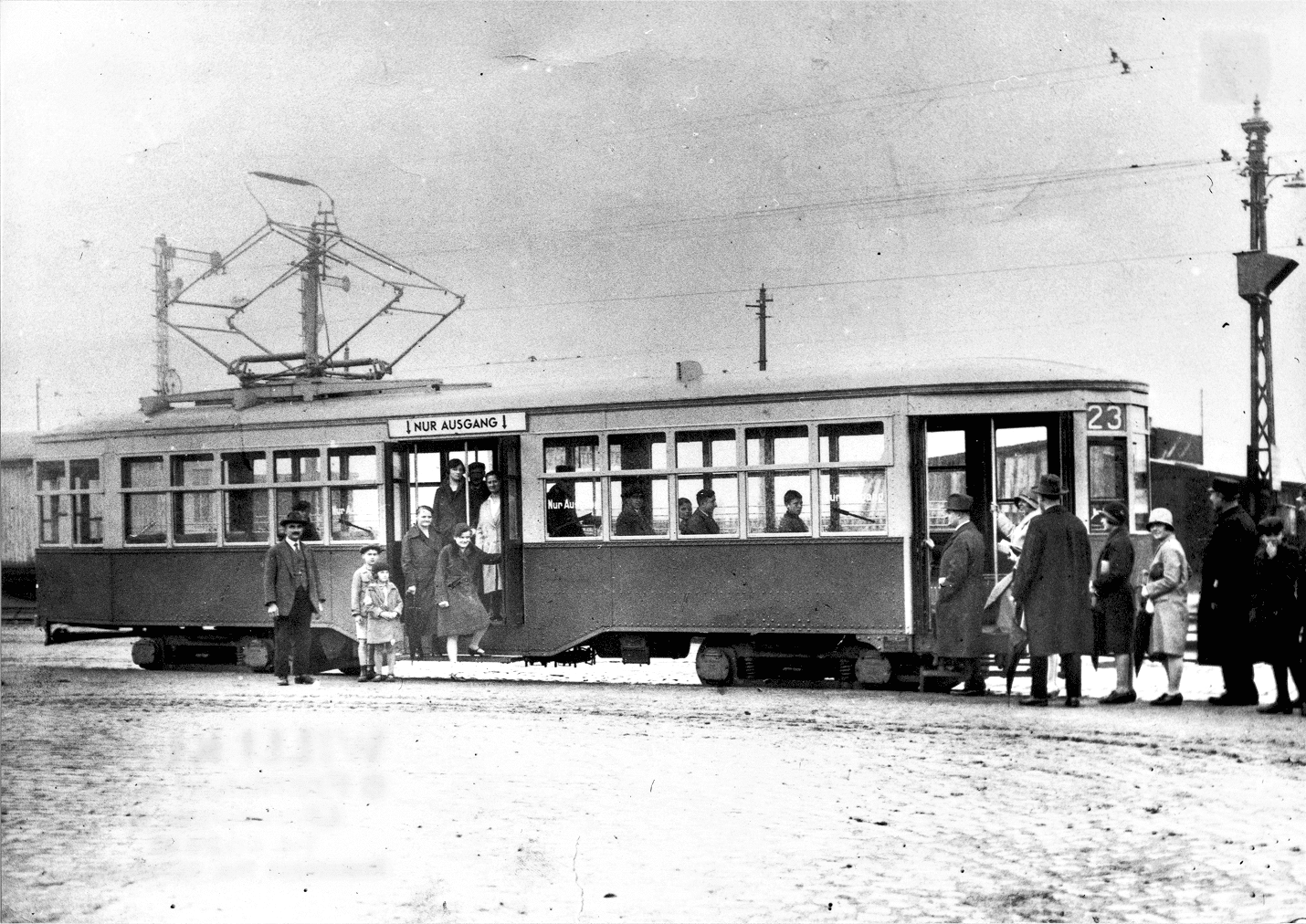

1929 the interesting trial operation with the “Peter-Witt railcar” built for the Milan ATM also took place, which the author of the newspaper article (right) referred to. Frankfurt rented the 1502 car from ATM and used it on line 23 between Heddernheim and Schauspielhaus on a trial basis. The aim was to test the practical usability of such a vehicle in terms of passenger behavior as well as possible staff savings and reduced workload for conductors.

However, these trial operations were not followed up by an order. At off-peak times, attempts were made to introduce one-man operation on the streetcars in order to reduce costs. This was only successfully implemented on the outer lines 33 to 36 (later also 31 & 38). – At the end of the 1920s, 11 bus lines were already in operation (A – K, DD + W).

1930-31 With regard to the efforts to rationalize operations, further attempts were made to save personnel after the experience with the Milan coach, which was not suitable for Frankfurt in every respect. For example, the C-carriage 363 was permanently connected to c-carriage 911; a gangway was created between the two vehicles for the conductor, who could thus operate two carriages instead of just one, thus saving a third of the train crew. This combination ran for a long time on Line 7.

After the successful experiment mentioned above, further conversions were undertaken. The D sidecar 600 was converted together with D-Tw 394 into an articulated car with automatic doors, whereby the Tw became 394a and the Bw became 394b. This combination often ran on line 6. Another double car was created from the two D-Tw 392 and 393 and was given the designation 392a/392b. From 2.11.1930 the streetcar came to Griesheim, see article from the Städtisches Anzeigeblatt of November 1, 1930 (bottom left). A report on the new line was published a week later in the same newspaper (bottom right).

1932-33 In these years, as in the two preceding years, the new housing estates on the eastern Wittelsbacherallee and around Ludwig-Landmann-Straße were connected to the streetcar network by master builder Ernst May by extending line 15 to Inheidener Straße on the one hand and line 2 from Hausen to Heerstraße on the other. In addition, the new IG Farben administration building was also given a rail connection by laying a link between the corner of Grüneburgweg/ Reuterweg and Eschersheimer Landstraße at Cronstettenstraße.

As a result of the National Socialists’ seizure of power, the Frankfurt tramway had to use the cumbersome name “Straßenbahn der Stadt des Deutschen Handwerks Frankfurt am Main” from 1933. As if that wasn’t enough, as was customary in all public companies at the time, the management levels were filled with forces loyal to the system, “assimilated” in Nazi German.

1934 to 37 In these years, all 50 f-cars and 10 g-cars were subjected to various conversions due to increased railcar requirements. Only the f-cars 1501 – 1503 remained sidecars, they were only upgraded as “fv” cars for the Taunusbahn lines. The rest were converted into traction units with the addition of motors, electrical equipment and current bars. In this way, CF and CFv railcars were created with the new numbers 31 – 53, as well as the additional F railcars 451 to 474. Finally, the g sidecars 1551 – 1560 were also converted into CFv railcars and given the numbers 54 to 63.

After the war, some of the cars were converted back into sidecars, while others were converted into other types of railcar. In 1937, the tramway was provided with new set-up and turning capacities in the Messe area, such as the block bypass via Varrentrappstraße and Rheingauallee, as well as its current separate track route in Hohenhollernanlage and Moltkeallee.

1938-39 From 1938, city tours could be taken by streetcar. A new line “0” was set up especially for this purpose, which circled the city center and Sachsenhausen from the main station (> exact route here). The double railcar 392, built in 1931, was prepared for the task because, as with the Ebbel-Ex today, Ebbelwoi was to be served to passengers during the journey. The “Ebbel-Ex” is therefore not a modern invention, as one might assume!

After corrosion damage due to a lack of renovation, the Obermain Bridge was rebuilt on 22.08.1938 was completely closed to streetcar and motor traffic, the (> Lines 7 and 19 both ended on the banks of the Main) [JPG, 468.17 KB]. This state of affairs continued for 11 years due to the burdens of war, before it was ended in 1949 after the bridge was completely renovated. 01.01.1939 colored roof lamps were banned on the streetcar (see left).

1940-41 Due to the constantly increasing shortage of materials, especially steel, which was primarily reserved for the armaments industry, and also due to the financial resources tied up in the war effort, investment in rolling stock and the rail network was inevitably cut back. As a result, the trains had to run on wear and tear.

A shortage of tires and fuel even led to the complete cessation of bus services in 1940, as published on the left in the Frankfurt city gazette. Nevertheless, a new streetcar line was set up at the end of 1940, which initially operated as the 23 E and became the 37 from December. This could have been related to the increased production for armaments purposes, as was the case in the Gallus district, especially in the Adler factories.

1942-43 In October 1942, a booster line 128 appeared in Offenbach’s cityscape, with the highest line number that ever existed in the Frankfurt/Offenbach streetcar network. One year later, in November 1943, the last new line before the end of the war went into operation in Offenbach, which was also the penultimate line in Offenbach It was the short, single-track connection in Bismarckstraße between the main railway station and Waldstraße. Originally, it was to be opened in 1927, together with the line in Waldstraße. It was not opened until 16 years later, in the middle of the war of all things. But why? From today’s perspective, this is inexplicable; perhaps only a visit to the Offenbach city archives could shed light on this.

Also in the autumn of 1943, the Allies launched intensified air raids on the two neighboring towns, which were ultimately followed by their complete collapse a year and a half later. Shortly before Christmas 1943, test runs were carried out with a Giessen trolleybus on the route of bus line 60 through the Roman city, which was now covered with overhead wires.

1944 The first city-owned trolleybus was used on line 60 from January 6, 1944. However, two months later it and three other vehicles were completely burnt out in an incendiary bomb attack on the Heddernheim bus depot, which led to line 60 being suspended again. Only when Frankfurt received four new trolleybuses from a delivery originally destined for Salzburg a quarter of a year later was operation resumed.

VEGETABLE TRAMWAY IN THE II. WORLD WAR

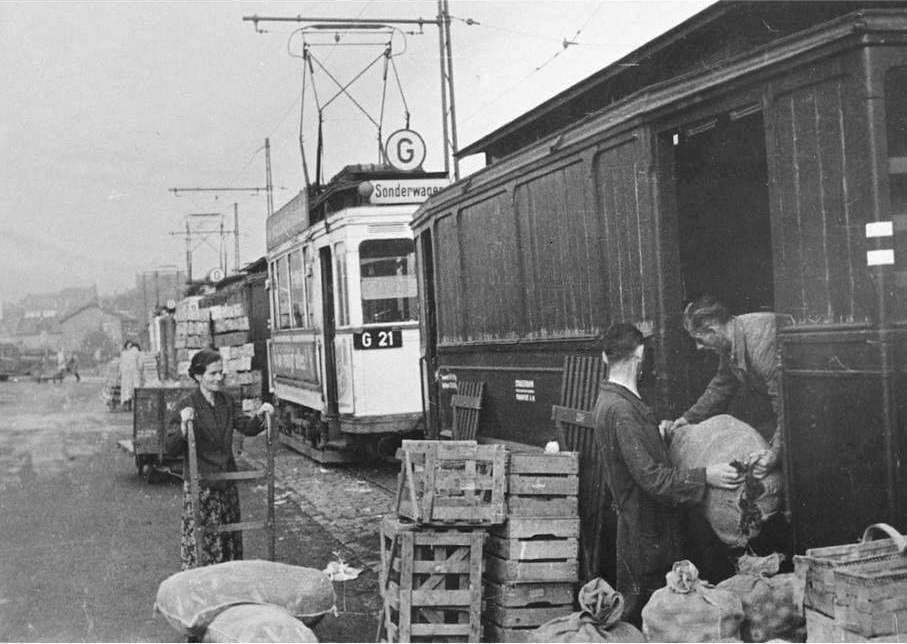

Loading vegetables at the wholesale market hall. The access road was reached by a branch from the Ostbahnhof – Riederhöfe line. In total, there were recorded transports to at least six city districts, which were named after the regular lines running there. The trains were lined up one behind the other for loading, so the C coach waiting in second position here led its train on the 21 line to Schwanheim.

This service required additional resources, which on the other hand proves the high efficiency of the Frankfurt tramway before 1945. In any case, it was extremely difficult to maintain operations because the constant destruction of tracks, contact wires, vehicles and other equipment constantly challenged the employees’ talent for improvisation.

Despite these unfavorable conditions, the streetcar achieved a record of almost 200 million “transport cases” in 1944, a figure never reached again in the post-war period.

With increasing motorization after the war, passenger numbers fell to 170 million by the end of the 1950s and finally leveled off at around 155 million at the end of the 1960s. It was not until 50 years later, in 2018, that the 200 million mark was finally broken.

In 1944, the streetcar fleet consisted only of cars from the A/B to H or c – h (Bw) series, built between 1899 and 1939. The average age of the railcars was 33 years, because over 2/3 were still from the early days and were outdated due to the lack of renewal before and during the war. The 20 J series standard railcars delivered in the same year did nothing to change this. They were delivered without engines and were only completed and put into service after the end of the war.

1945 The constant bombing raids of the previous years continued in 1945. In total, the Allies dropped 26,000 tons of bombs on Frankfurt during the Second World War. After the air raids from January to March, especially after the bombing raid from 09.03.1945life in the city largely came to a standstill. This also applied to streetcar operations, whose infrastructure was destroyed almost everywhere, including the main workshop at the Bockenheimer Warte (left).

May 24, 1945 Two streetcar lines resumed operation after the tracks had been cleared of the coarsest debris, in some cases by detours, namely lines 10 and 12, whose route at the time is shown below.

From July 02, 1945 15 lines were running again on 40 kilometers of track. – During the war, overhead lines had often been robbed of their suspensions and torn to the ground due to destroyed building walls. In order to quickly restore operational readiness, it was therefore often necessary to erect temporary wooden masts at the side of the road, from which the contact wires, which had previously been anchored to the walls of buildings, could then be suspended. Such temporary structures could still be found in some streets 20 years after the end of the war.

Another aggravating circumstance came in spring of 1945 for the company: The occupying power had declared the northern Westend and parts of the Nordend to be restricted military zones, which meant that the lines in Eschersheimer and Bockenheimer Landstraße, Reuterweg and Oederweg could not initially be used.

This meant that western and northern areas of the city were cut off from the city center. The boundary was set back a few meters in the west end at the end of July so that the line to the western suburbs could be used again. A different solution had to be found for the north.

This resulted from a decree by the American military administration, which demanded the construction of a streetcar connection from Eckenheim via Marbachweg to Dornbusch, which was to serve the transportation of its servants. Because new track material was not available, the tracks of line 11 in Koselstraße, which had been closed in 1939, were torn out and a track was laid in Marbachweg, with a siding at Kaiser-Sigmund-Straße. This was the first new line to be built after the Second World War, albeit involuntarily.

She left on 15.07.1945 with the “ROUNDUP” line 39, reserved exclusively for the US military, which connected the headquarters at Bremer Platz (formerly IG Farben) with the barracks in Preungesheim, and 3 weeks later with the main railway station. Finally, the Frankfurt streetcar was also given permission to run other lines via the new connection, so that the north of the city was served from 06.09.1945with line 23 via Eckenheim, finally got a connection to the city again. Line 23 E followed from October 1, 1945, while the FLAG lines were only able to run through again nine months later. The track that emerged from the emergency situation still exists today, apart from the siding, but has only been used internally since 1978.

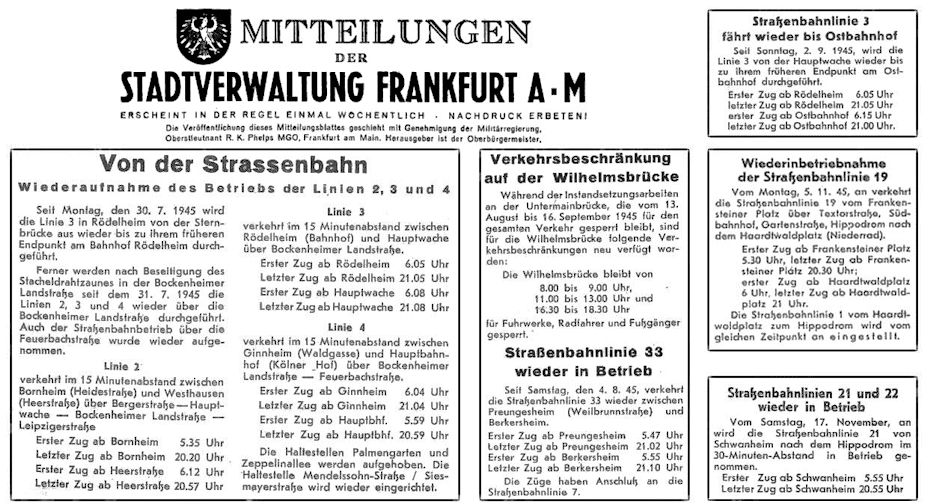

▼ In the course of 1945, these reports concerning the streetcar appeared in the Stadtanzeiger ▼

RECONSTRUCTION AND NEW CHALLENGES

Autumn 1945 The route network gradually grew back together, 60 km were now covered by 18 lines. By the end of the year, there were 24 again, including three special lines. A second “ROUNDUP” line to Heddernheim (13) and the 26 (HVZ, Lokalbahnhof – Offenbach/Waldstraße) had been added to the line 39 already mentioned above, all three of which were reserved for the US armed forces only. When the new line in Marbachweg was allowed to be used by “public” lines from autumn 1945, the connection from the city center to the northern districts and to the Taunus was re-established, albeit via a detour via Eckenheim. Line 24 was still interrupted at the blown-up highway bridge near Niederursel, where passengers had to walk a short distance to continue their journey. This gap in the network was not closed until 1946. In the fall, the 54 was the only bus line to resume service from the Nied streetcar terminus to Höchst.

1946 Staff shortages as a further consequence of the war led to severely restricted traffic on the TVZ for most of the year. There was also an acute shortage of wagons and electricity. Two separate parts of the network also continued to exist side by side; Sachsenhausen was still without a connection to the North Main part of the network until 1949. The routes changed very frequently in the first post-war period.

The continuing shortage of materials caused problems for the streetcar. Among other things, there was no window glass, which is why destroyed window panes were replaced with cardboard. A lack of tires and fuel as well as the temporary confiscation of most buses by the Americans prevented the reopening of further bus routes. The problems were exacerbated by the passengers themselves, who unscrewed light bulbs from the interior lighting in an attempt to “get home to my kingdom”!

▼ Notices published in 1946 by the city administration on current changes to the streetcar system ▼

1947 Although the shortage of materials continued unabated in 1947, the delivery of Fuchs/BBC standard tramcars (type J), which had already begun three years earlier, was now continued. A further 25 railcars of this type were added to the existing ones, this time fully equipped so that they could be used immediately. The 20 incomplete ones were now gradually fitted with D 58 wk engines, which had already proved their worth in the C cars.

The company thus had a total of 45 new railcars at its disposal. In the same year, the former Frankfurt body factory in Rebstöcker Straße also built the 1401 sidecar on the remaining chassis of a (d?) car destroyed in the war. The car was renumbered 1000 in 1949 because the planned new “e” series car type was to occupy the 1400 numbers.

In 1966 it was incorporated into the “e” series and was given another new road number, this time 1400, which it was allowed to use until it was taken out of service in 1972.

Even among the electric sidecars, it remained an exotic model, as it had two wooden benches lengthways on the window sides of the interior and four windows instead of three. This and its greater length meant that it differed greatly from all other e-coaches. Here it is in the picture, in front of the Eckenheim depot in the early 1970s.

However, this only eased the overall situation slightly, as 1947 brought with it a number of other problems, not to mention the “hunger winter” of 1946/47 with its extreme cold. In view of the miserable staffing situation, Sunday services had to be suspended for months. More details in the “Mitteilungen der Stadtverwaltung Frankfurt”.

1948 Only with the currency reform on 21.06.1948 the situation improved noticeably. With the end of the preceding inflation, the reconstruction that had begun gained speed and the shortage of materials gradually came to an end. Between 1948 and 1960, a total of 111 million Deutschmarks was invested in rolling stock, track and track systems, but loans had to be taken out for 2/3 of the sums.

Together with the new additions of the previous year and the vehicles repaired in the company’s own workshops, the number of vehicles in service increased to 140 railcars and 225 streetcar sidecars as well as 35 buses and coaches, but this was still a far cry from the pre-war stock. However, it was unmistakable that things were now slowly but steadily improving again.

1949 – June 05: The first new line after the war is opened in Offenbach, and unfortunately it was to be Offenbach’s last. It ran from the Dietzenbacher Straße loop to the beginning of Brunnenweg before Tempelsee, using a former industrial railway track. Line 27 took over the route.

On June 21: The reconstruction of the Obermainbrücke bridge is completed and Sachsenhausen is finally reconnected to the rest of the network with lines 7, 9, 16 and 19.

On July 24 the Untermainbrücke bridge was also put back into operation (lines 1, 4, 8, 11).

A reconstruction program was launched to counter the still dramatic shortage of cars. This involved putting new bodywork superstructures on chassis that had been destroyed during the war. This resulted in a new railcar series K(A) (= superstructure type), in the construction of which DÜWAG, BBC, AEG and Siemens were involved. The first 14 vehicles arrived in 1949, 26 more in 1951 – 1953. 12 sidecars similar to the Tw were built at Westwaggon in Cologne, which were initially designated “ka”, but from 1963 were then called “gk” to distinguish them from the k cars converted to “ka”, because they had received chassis from destroyed (f or) g sidecars .